Symbiotic bacteria living inside insects have been found with the smallest genomes ever recorded for a living organism, pushing the boundaries of what defines minimal life. The discovery challenges our understanding of how organisms can survive with severely reduced genetic material and raises questions about the evolutionary path from free-living microbes to cellular components like mitochondria.

The Ultra-Reduced Symbionts

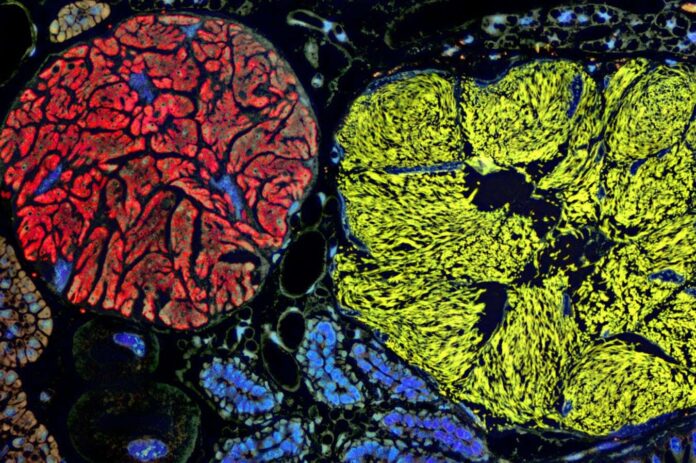

Planthoppers, insects that feed exclusively on plant sap, rely on symbiotic bacteria to supplement their nutrient intake. Over millions of years, these bacteria have become so intertwined with their hosts that they reside within specialized cells in the insect’s abdomen, providing essential nutrients the insects cannot obtain from their sugary diet. As a result of this dependence, the bacteria have drastically shrunk their genomes – the complete set of genetic instructions – to a fraction of their original size.

Researchers led by Piotr Łukasik at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, analyzed DNA extracted from 149 insects across 19 planthopper families. The team sequenced the genomes of two key symbiotic bacteria, Vidania and Sulcia, finding them to be incredibly small: less than 181,000 base pairs long. In contrast, the human genome contains billions of base pairs. Some Vidania strains measured just 50,000 base pairs, making them the smallest known genomes for any life form, edging past the previous record holder, Nasuia.

The Edge of Viability

At such a reduced size – with some strains possessing only about 60 protein-coding genes – these bacteria exist on the scale of viruses. For comparison, the genome of the virus behind COVID-19 is around 30,000 base pairs long. This raises a fundamental question: at what point does a highly reduced microbe cease to be considered fully alive? The distinction between a living organism and an organelle, such as mitochondria, becomes increasingly blurred.

The bacteria’s primary function in this symbiotic relationship is to produce phenylalanine, an amino acid crucial for building and strengthening insect exoskeletons. Łukasik’s team theorizes that massive gene loss occurs when insects acquire alternative nutrient sources or when additional microbes take over those roles.

Evolution and Organelle Origins

The symbiotic bacteria have been co-evolving with their insect hosts for approximately 263 million years, independently evolving toward extreme genome reduction in different planthopper groups. This evolutionary trajectory mirrors the origins of mitochondria and chloroplasts – energy-producing organelles within animal and plant cells that descended from ancient bacteria. These organelles also reside within host cells and are passed down through generations.

While some researchers, like Nancy Moran at the University of Texas at Austin, are open to classifying these highly reduced bacteria as organelles, differences remain. Mitochondria are far older, having emerged over 1.5 billion years ago, and their genomes are even smaller – around 15,000 base pairs. Moreover, mitochondria are distributed throughout the organism, while these symbiotic bacteria remain confined to specialized cells.

Łukasik suggests that both these bacteria and mitochondria simply occupy different points on an evolutionary gradient of dependence. He suspects that even smaller symbiote genomes remain undiscovered, further blurring the lines between life, symbiosis, and cellular integration.